Modernization of Ottoman Public Education

And the Role of Darulmuallimin

Historically it is not appropriate to periodize Ottoman history with progress-stagnation and declineperiods. Historians have problematized the idea of decline in regards to the Ottoman state. Before we can establish if the Ottoman Empire was in decline or stagnation, we must first investigate the Ottoman caliphate’s economic, military, and political situation. The late Ottoman period can also be viewed as being in a state of equilibrium that is not simply static, rather there is a contestation of power at various levels of society. Until the 18th century, the Ottomans did not openly acknowledge their European counterparts’ supremacy in economy, science, government, and education. Indeed, as the Ottoman state faced the great burden of battles and failures against European troops in the 18th century, they deliberated and commissioned papers to study various solutions that could be presented to correct their shortcomings.

This thesis will discuss problems concerning the Ottoman renaissance project. In particular, it will focus on educational reform which aimed to regain the competitive strength of the state. In this paper, I am going to examine the Darulmuallimin schools, whereby teachers were trained to impart the proposed reforms of the Ottoman state. At the time of its inception, it was considered vital for the salvation of the Ottoman educational system as the state felt itself lagging behind its European rivals. Moreover, I will look at Darulmuallimin’s struggle against the hegemony of the Madrasa system and its dogmatic educational system.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Sultan Mahmud II and his bureaucrats wanted to embark on an ambitious reform program. The old ways of operating the state were deemed inadequate. Three major areas were considered to be in need of reform or were partially abolished. The old religious authorities and lawmakers (Ilmiyye), the bureaucratic class (Kalemiyye) and the military class (Seyfiyye), the pillars of power that had governed the Ottoman state for several hundred years were erased, as was the case for the Janissaries, or they saw their powers severely curtailed in the case of Ilmiyye and Kalemiyye classes.

Such Ottoman governmental initiatives, which contemplate the need for progress and innovation, began in the 18th century with the modernization of the educational system. The main focus was on restoring the state’s strength, which had deteriorated, particularly in the military, in comparison to Western inventions and rising power. As a result of this, educational reforms were employed firstly in engineering institutions related to the imperial army and its military schools like the naval academy of the state. The major goal, however, was not to build a new system, but rather to emulate Western institutions in order to meet their norms.

To understand this change and its educational foundations, we must return to the time of Mahmud II, who significantly shaped the traditional institutions of the Ottoman state by eradicating the Janissary troops and classical army and their supporters (mostly the old ulema), transforming the old ulema class and creating the Aydin (literate and scholarly) class, renewing the classical palace and land system, and laying the groundwork for the Ottoman public educational renaissance. The transformation of existing institutions occurred concurrently with the establishment of new institutions; nonetheless, many of the old institutions remained, albeit in a reformed form. The paradoxical existence of conventional and modern schools resulted in successive generations of students at odds with one another due to ideological differences and diverse viewpoints garnered from their schools.

Dualism among Ottoman intellectuals, their imbalanced characteristics that could not belong to either East or West, and the 19th century’s political turmoil created a turbulent era for the Ottoman state and its educational endeavor.

The modernization of Ottoman public education was based not only on the executive dictates of the Padişahs (Emperors), but also on consultation with a diverse range of intellectuals and bureaucrats. Sadık Rıfat Pasha was one of the first men to highlight the role of education in modernization, and he was a key instigator of the Tanzimat platform at the time. He described the driving force behind European progress as follows: They (Europeans) value education above all else, and it is hard to accept a group of people as a nation unless they can read in their language. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, attempts were made to govern the public education system, with rüşdiyes (secondary schools) being the first to be established. The challenge was that the state was unable to establish a standardized structure to secure sufficient number of teachers for the newly established schools. Darulmuallimins (teachers’ training schools) were established in 1848 under the direction of Tanzimat aydins. The first Darulmuallimins were to raise the teachers that rüşdiyes desperately required. It was followed by the establishment of Darulmuallimat in 1858 for the training of female teachers, and Darulmuallimin-i sıbyan (primary school teacher training program) in 1868. As the modernization of the public educational system commenced, traditional madrasa and ulema became competitors to these schools.

Ex-Darulmuallimin as the Madrasa versus Modern Darulmuallimin:

Madrasa, as an Arabic word, comes from the verb studying and it means; the place where studying takes place. madrasa, as an institution, came with the Anatolian Seljuks and Beyliks to Western Anatolia and transferred to Europe through the Ottomans. For centuries, the madrasa was the main educational facility of Islamic civilization including the Ottoman state. Primary school programs and for example, Darulhadis (Islamic master program after the madrasa) were found in accordance with the madrasa institution.

The fundamental goal of the madrasas was to prepare pupils for the hereafter rather than the world, and it included a combination of religious education, math, philosophy, astronomy, literature, and various arts and subjects. As a result, there was no clear distinction between teaching Islamic knowledge and all other forms of disciplines in the madrasa. To be a professional in a specific subject, such as medicine, a person must first obtain Islamic education for a long period of time before gaining experience as a doctor. In the Madrasa, there was no clear class system, but classes were organized around certain books that were lectured by a scholar; each class was based on a book that a student studied and memorized. That is, there was no order in terms of the pupils’ gradual progression, nor was there a curriculum developed for the youths. When the specific books were taken, the class (circle) and the subject were over.

During Fatih the Conqueror’s reign, the madrasa was the most capable institution competent in enlightening people on both religious and scientific concerns. Fatih collected renowned intellectuals from around the world and invited them to debate in front of students, and he participated in these discussions, advancing critical thinking and cultural interchange in the Ottoman realm. He commanded that famous Greek and Latin books, as well as Arabic and Persian texts, be studied and read in madrasa circles. Suleiman the Magnificent carried on his grandfather’s legacy by experimenting on educational advancement and opening new madrasas with master programs (Darülhadis and upper medicine program) near the Süleymaniye Mosque. By the end of the 16th century, certain scientific books had been excluded from Madrasa lists, because some ulema members believed that the madrasa’s major existential function was to provide religious education. Kadı Zade’s (a famous family in Ottoman history mostly consisting of Islamic scholars) were good examples of reactionary ulema groups that resisted the teaching of mathematics, philosophy, and sciences related with the nature in the madrasa curriculum.

Takiyuddin, established the most advanced rasathane (observatory) in Istanbul with Sultan III Murad’s donation of 40,000 gold pieces. Later, Kadı Zade Ahmet Şemseddin (the Empire’s chief religious authority) opposed to his study and accused him of practicing sorcery in the observatory. Takiyuddin was later found to be a non-follower (disciple) of Kadı Zades (didn’t follow their rules), which is why he was accused of interacting with stars and elves in space. Rasathane was destroyed by the navy’s artillery bombardment as a result of the intervention of the ulema known as Kadı Zades.

When Europe was in the dark ages and scientists were suppressed by the Catholic church, the situation was opposite in the Ottoman and Middle Eastern territories. However, in the 17th century, a new style of scholasticism evolved in the madrasas that was similar to the format of old European scholasticism. Muallim Cevdet, a graduate of the madrasa system and a prominent member of the aydin class, discusses the madrasa’s scholasticism and its flaws in three key features: (1) Following doubtlessly one of the Western or Eastern scientific books, a scholar or a sect; (2) Not criticizing or renewing the previous work according to the needs of society, time, and cultural dynamism; (3) Sticking on the books to acquire knowledge rather than applying experiments in nature.

Due to the arrogance of Muderrises (madrasa teachers) and the Ulema class, the second half of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century were the lost years for the Ottoman educational system. While Europe succeeded to free itself of scholastic reactionism, the ideas of Aristo and Oklides heritage was recreated in the madrasas. At the end of the 17th and 18th centuries, there were discussions about replacing astronomy and arithmetic classes on the curriculum, but the ulema could not come to an agreement. The basic system of the madrasa was so reliant on the personal decisions of ulema, who could cancel or reinstate any book on the curriculum. For centuries, some people, such as the Kadı Zade ulema family, were hostile towards engineering, astronomy, philosophy, and natural science studies in madrasas. This stemmed from the madrasa system’s systematic problem, since it lacked the ability to make provisions for the conservation of books, and the was not immune to manipulations of individuals.

Apart from these problems, the language in which the lectures were delivered was a major impediment to the students’ progress and understanding. Despite the fact that Turkish was the most frequently used language in the palace, bureaucracy, and society, the texts in the madrasa were read in Arabic. The preparation lessons for teaching Arabic included memorizing of Arabic grammatical rules and syntax, as well as calligraphy of Arabic characters. After students learned Arabic, they began to memorize passages, repeated them, and copied them to pages in order to pass examinations. At the end of this education that took almost 13 years, students mostly were not able to speak or write in Arabic. The basic education before the madrasa was provided in the Sıbyan Mektebi (children’s school) or, Mahalle Mektebi (neighborhood school) for children aged six to ten. Problems related to language arose in these primary schools since kids were first taught how to read in Arabic script. When students began reading the Quran, they began to memorize and recite it, and they later took calligraphy classes. Yet students at this level did not grasp the essence what they read or wrote. The Ottoman traditional education system was based on mimicking and memorizing ancient literature. Children were unable read and utilize their mother tongue from the start of their education, limiting their ability to generate ideas and engage in critical thinking; instead, they would repeat and replicate texts.

Fatih and Bayezid specifically stated the importance of enrolment of orphans and the poor in these schools to embody a charity culture in the education system. The characteristic of charity-based education formerly expedited the foundation continuums of these schools, but was later restricted by the state’s possibility of improvement and centralization. Because of the major issues described above, the impunity of madrasa and sibyan mektebi as elements of the charity complex damaged the potentials of young talents for centuries all across the empire.

According to İhsan Sungu, the Head of National Education, pedagogically perusing the subject of children’s first year of education, beginning with reading and memorizing the Quran, was a great burden that a child could not handle. Even in countries where Arabic was the mother tongue, it was not deemed suitable to begin the first year of school with studying the Quran. Despite the fact that several aydins and officials underlined the issue, ulema remained unconvinced, and the system persisted until the end of sibyan schools.

The typical curriculum of primary school covered learning how to write and read the Arabic alphabet, familiarizing with the Quran and basic Islamic jurisprudence, as well as memorization of some short pasaages from the Quran. In the primary madrasa pupils improved their skills and knowledge in Arabic writing, Quranic lessons, basic mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence, and basic ilmihal (catechism). Middle education was in the inner and outer madrasas and these madrasas covered Arabic grammar, writing, engineering basics, calculus and mathematic, debate, logic, and reading of Şerhi Fenari, Metali Şerhi, Haşiyei Tecrid and kalam (Rational philosophies). At the high school level, Tetimme madrasa started with logic, Şerh-i Miftah (Explanation of Key) and Muhtasar Meani, Mutavvel, Method of Islamic jurisprudence, and they were followed by reading and memorization of approximately 20 traditional books. In the license, Sahn-i Seman and Sahn-i Süleymaniye contained medicine, mathematics, physics, kalam, astronomy, hadith(sayings of Prophet Muhammad) method lessons.

Lessons were delivered by highly qualified persons in the early days of the madrasas, and madrasas raised prominent Ottoman intellectuals, doctors, architects, Islamic scholars, and engineers. Ali Suavi, a well-known Tanzimat aydin, completed the classical madrasa with honors but enucleated that, despite having taken all Arabic lessons, he was unable to give a speech in Arabic or compose a literary work in Arabic. All of these 13 years could have benefited his Arabic, but they did not.

The Sultan Abdulhamid II purposefully ignored madrasas during his reign – they were neither repaired nor regenerated. As a result, the demise of Madrasa began during the reign of Abdulhamid II. The madrasa reformation plan failed, and when the Turkish Republic was established, Mustafa Kemal closed the madrasas. For generations, madrasa could not have the confidence to critique itself, which eventually led to its end.

The Century of Education:

Aside from methodological issues, Ottoman society perceived of education as a luxury. Parentstreated children as an additional workforce in the fields and workshops. This was one of the reasons why so few pupils attended school. Also, In remote places and villages, there was a scarce of educational facilities.In the edict of 1824, one can see Mahmud II’s enthusiasm for restoring order and modernizing education. He submitted an imperial order of compulsory education for every child in the state and required the parents to let their children into the schools. He specifically labeled the ones who did not send their children as sinful people. He further warned the irresponsible parents on the topic that they will be judged in the Day of Judgement to convince parents for his campaign with the Islamic understanding.

The fundamental principles of education were first discussed in 1838 by the political power under a bill (draft) issued by the Meclis-i Umur-u Nafia (Council of Public Works). The bill describes education as a factor leading humans to higher levels of welfare, helping them to reach a content life, and contributing to the development of the Ottoman state. This turning point in education was followed by the foundation of Mekatib-i Rusdiye Nezareti (Ministry of Secondary Schools) under the Evkafı Humayun Nezareti (Organization responsible for the Administration of Foundations) on March 11, 1839, and Esad Efendi was appointed to the ministry. Even though in the Tanzimat edict, there was no room or emphasis on education, in the Royal Edict of Reform (1845 Hatt-i Humayunu) a contingent of seven members started to discuss educational reforms. The members, having a good grasp of judicial, military, and administrative knowledge, started the same year to investigate available schools and provide the opportunities to open the new ones under a decree by Bab-i Ali (Sublime Port).

From 1727 onwards, the Ottoman state turned its face to the West to implement the innovations but no one could have the courage to interfere with the madrasa system. The only way to make absolute variance was turning madrasas into modern schools or modernizing them but none of the sultans or bureaucrats could undertake an action. Even in the new schools, the spirit of the madrasa was recreated by setting similar forms of Arabic and Islamic lessons. Until 1846, in the Mektebi Maarif-i Adliye (Law Department) and Mektebi Ulumu Edebiyye (Literature Department) giving classical Arabic lessons would be counted as a renovation. When we come to 1848, it was clear that Darulmuallimin should be formed to train teachers for the rüşdiye mektebs, which could not progress due to the attitudes and understanding of previous school teachers. A dualist educational dilemma arose with the formation of rüşdiyes and their newly created curricula. It should be highlighted that not only did the state fail to anticipate the problem of dualism among modern and old schools, but the state also remained silent due to the silence of ulema and muderrises (madrasa professors).

The first darulmuallimin was established in 1848, but it did not survive until the reign of Abdülaziz. Darulmuallimin-i sıbyan (primary school teacher training program) was founded in 1858. Following darulmuallimin-i sıbyan, ibtidaiye’s (primary schools) and rüşdiye’s curriculums were regulated, and darulmuallimins were established for both divisions. However, the first notable change in the curricula of the newly formed darulmuallimins was the elimination of Arabic courses in favor of French studies. In darulmuallimin, the curriculum began to deploy formation and pedagogy courses alongside Islamic value lectures. According to Selim Deringil, the major goal and purpose of all those curriculum designs was to unify all citizens of the state who belonged to different religions and races under the ideal of Ottomanism and to guarantee Ottoman unity by training them together.

Because of a lack of background preparations for educational reforms and a shortage of trained teachers, Mahmud II’s initiatives failed to elicit the necessary response. Even in Istanbul, there was insufficient infrastructure to support large-scale instructional programs. When the new system was being developed, and darulmuallimin-i rüşdiye was established, the teachers for these modern schools were not academically qualified. The remainder of the academics were removed from madrasas, resulting in the collapse of the anticipated educational overhaul.

There was little emphasis on education in the Tanzimat edict; but, in islahat 1856, it was issued that every school shall be open to everyone. The sects might create their own private schools, and all of the teachers and school programs would be dependent on and coordinated by Maarif Nazarı (ministry of education). The decisions took time to be executed, and on February 22, 1867, the French government wrote a diplomatic note to the Ottoman State, requesting that the changes stipulated by the Imperial Edict of Reorganization and the Royal Edict of Reformation be carried out (Tanzimat and Islahat Royal Decree). In the name of the French government, Jean-Victor Duruy ordered the necessary procedure, such as reorganizing maintenance and encouragement of Christian schools, establishing libraries for the benefit of all citizens, legalizing co-education, and opening new schools. France expected the Ottoman education system to be merged with all inhabitants and transformed into a non-formal structure. Based on Duruy’s concept, the Maarif-i Umumiye Nizamnamesi (Regulation for Public Education) was established in 1869, bringing an organized, precise program and structural reforms to education. The regulation of public education also outlined the essential norms of the education system, such as the age limits for children enrolling in schools, the curricula for new opening programs such as (ibtidai and rüşdiye), and the obligations of teachers. Great Darulmuallimin (teacher training schools for master programs) opened the same year as maarifi umumiye nizamnamesi. Great darulmuallimin’s program included science and literature departments. Despite the fact that the opening of the great darulmuallimin was authorized in 1846 by the decision of the Meclis-i Vala (courthouse parliament), it was not implemented until 23 years later.

Darulmuallimin:

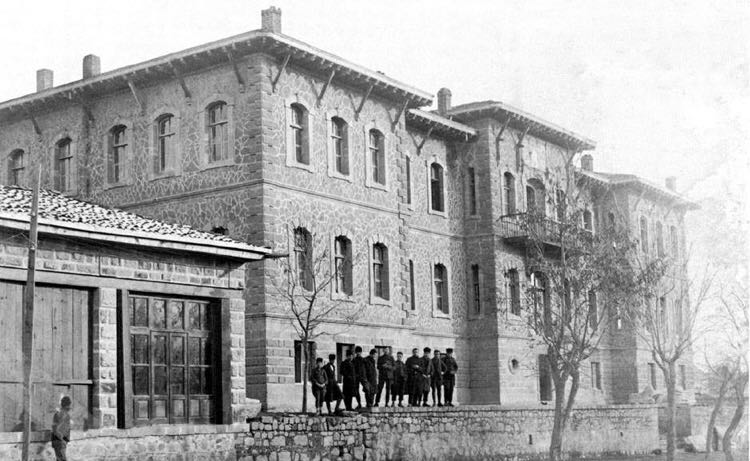

During the Ottoman state’s final era, it was discovered that training instructors who would transmit the state’s new ideology was critical in the process of modernizing the education system. It had been planned since the reign of Mahmud II to establish the Darulmuallimins to train new teachers, but the foundation of the Darulmuallimins was laid on March 16, 1848 in Istanbul’s Fatih neighborhood. The first Darulmuallimin was inspired by the design of French teacher schools. Ahmed Cevdet Efendi was elected principal of the first school. He created a document that explains the Darulmuallimin’s foundation and mission:

The Darulmuallimin’s initial curricula and charter were as follows:

Places which Darulmuallimins were found:

|

Name of the School |

1899-1900 |

1900-1901 |

1903-1094 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Edirne |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Adana |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Ankara |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of İzmir |

2 |

2 |

5 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Bursa |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Diyarbakır |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Salonica |

7 |

6 |

6 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Sivas |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Trabzon |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Kastamonu |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Konya |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Manastiri |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Loannina |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of San’a |

– |

4 |

4 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Ta’iz |

– |

– |

3 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Baghdat |

– |

– |

4 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Kosovo |

– |

– |

3 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Debar |

– |

– |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Triplolitania |

– |

– |

1 |

|

Darülmuallimin of Mosul |

– |

– |

2 |

Darulmuallim-i Sıbyan and Darulmuallim-i Ibtidai:

Influencing youngsters aged six to ten required a shift in the dynamics of Ottoman society and public schooling. When the ibtidai (starting) primary schools began to operate, the state did not close the sıbyan mektebs. The sibyan mektebs were counted as charity foundations under the umbrella of Evkaf Nezareti(Ministry of Non-Profit Organizations), making them nearly untouchable for a long period. In 1868, the first teacher school for modern primary schools was founded. In 1875, Darulmuallim-i sıbyans could be found in tens of provinces within the state.

Darulmuallim-i Sıbyan’s 1868 program included Islamic knowledge, reading, calculus, history, geography, dictation, calligraphy, Turkish grammar, and innovative spelling methods.

Basic calculus, morals, and basic geography teachings were incorporated to the Quran lessons from that point forward. Following this accomplishment, the ministry of education desired to rebuild the sıbyan mektebs’ system and educate its instructors. Sıbyan-i Muallim Mekteb-i (primary school teacher training school) was discovered in addition to Darulmuallim-i sıbyan. Basic calculus and Turkish reading-writing abilities were also critical in these schools.

Following the release of Maarif-i Umumiye Nizamnamesi(The Regulation of Public Education), Abdülaziz’s decree led to the formation of Darulmuallim-i Sıbyan in Istanbul, and 50 students were registered for the monthly scholarship of 30 piastres. The purpose of opening darulmuallim-i sibyan mektebi was issued that necessity of regulating primary education in sıbyan mektebs is more important than inventing any other darulmuallimin.

The darulmuallim-i sıbyan mektebi entrance exam included Arabic grammar, logic, Persian, and calculus. Darulmullim-i sıbyans were established at the end of Abdülaziz’s reign at Konya, Crete, and Bosnia. By 1876, there were 17 officially established darulmuallim-i sibyans.

Büyük Darulmuallimin (Upper Darulmuallimin):

During Sultan Abdülaziz’s reign, the note issued by the French government to the Ottoman state in 1867 was a driving factor for the change of educational rules. One of the reasons that all educational facilities were unified under the nizamname could be the emphasis on teacher training and overall attention to education. Darulmuallimin, Darulmuallimat, and Darulfunun (Science School) were designated as master programs under Article 51 of the charter. Clause 52 states that the opening of Great Darulmuallimin, which includes secondary and high school teacher departments, would be divided into literature and scientific faculties. The rüşdiye was planned to be divided into Muslims’ and non-Muslims’ schools.

Rüşdiye (elementary), idadi (high) and sultani (another form of high school) schools’ curricula were mentioned in clauses 54, 55, and 56:

For the rüşdiye schools;

For the idadis;

For the Sultanis;

Clause 60 states that students of the darulmuallim-i rüşdiye branch would receive 80 piastres, students of the idadi branch would receive 80 piastres, and students of the sultani branch would receive 120 piastres as pocket money.

Certain essential articles of Darulmuallimin and Darulmuallimat according to the Ottoman Educational Annuals were:

Because of the pressing need to regulate the army and the disintegration of the administrative system throughout the centuries of modernisation, the state focused primarily on training boys. As a result of the gender separation in schools, women’s schools were established later on. However, after the establishment of a girls’ secondary school, the authorities recognized the need for female teachers. It took time for the first school to open, but in 1870, the first Darulmuallimat (Women Teacher Training School) was established. Darulmuallimat was to be founded in the 1870s to train teachers for the Kız Mekatibi Sıbyaniye (Girls‘ Primary Schools) and rüşdiye.

The school’s initial curriculum included Ottoman language grammar, teaching methods, a compulsory elective language lesson, morals, accounting, Ottoman history, geography, public works information, music, and needlecraft. Between 1873 and 1911 the school produced 737 graduates.

Abdülhamid and Darulmuallimin:

Sultan Abdülhamid II and his policy of public education advancement greatly influenced the expansion of darulmuallimins. Darulmuallimins began to appear in all areas of the Ottoman state. Darulmuallimin-i rüşdi, sıbyan, and aliyye diverged throughout Sultan Abdulhamid’s reign, with each focusing on its own activities. The program of darulmuallim-i sıbyan in (1899-1900) is listed below:

|

Name of the Lesson |

First Year |

Second Year |

|

Quran, Tajweed and Islamic Law |

4 |

3 |

|

Turkish Grammer and Spelling |

3 |

– |

|

Teaching Method |

– |

1 |

|

Prose |

– |

2 |

|

Arabic |

2 |

2 |

|

Persian Grammer and Gulistan Story Book |

2 |

2 |

|

French |

– |

1 |

|

Calculus |

2 |

2 |

|

Science |

1 |

1 |

|

Geography of Ottoman and General Geography |

2 |

2 |

|

İslamic History |

2 |

1 |

|

Calligraphy |

1 |

1 |

|

In Total |

19 |

18 |

Certain guidelines of darulmuallimins under the reign of Abdulhamid II are as follows:

The program of darulmuallim-i rüşdi is stated below:

|

The Name of the Lesson |

First Year |

Second Year |

|

Turkish Gramer |

1 |

– |

|

Pedagogical Formation |

1 |

2 |

|

Turkish Writing and Composition |

1 |

1 |

|

Arabic |

3 |

3 |

|

Persian |

1 |

1 |

|

French |

2 |

2 |

|

Calculus |

2 |

1 |

|

Bookkeeping |

1 |

2 |

|

Algebra |

1 |

1 |

|

Engineering |

1 |

1 |

|

Philosophy |

1 |

1 |

|

Biology |

1 |

2 |

|

Geography |

2 |

1 |

|

History |

2 |

1 |

|

Calligraphy |

1 |

2 |

|

Painting |

1 |

1 |

|

Islamic Sciences |

– |

2 |

|

In Total |

22 |

24 |

For generations, the curriculum of madrasa, the Ottoman state’s regular school and teacher training institution, remained largely unchanged. The madrasa, being the dominant institution of the education system, did not have a competitor facility until the 19th century’s darulmuallimins and rüşdiyes.

However, the curricula shown above pose severe problems to understanding of the madrasa’s restricted world view. The philosophy, physics, math, and astronomy teachings were blended with Islamic lessons that reflected Sultan Mehmed II’ Sahn-i Seman’s traditional madrasa system. The process of curriculum changes could be defined as the 19th century’s evolutionary epoch. Darulmuallimins became the link between the madrasa education system and modern Turkish schools at this period. Abdulhamid’s tenure aided the Turkification of the school system and the central bureaucracy in particular.

Historians, on the other hand, proposed numerous explanations based on the curricula variations of darulmuallimins and rüşdiyes in the 19th-century Ottoman state. According to Fortna, geography studies in sıbyan and rüşdiye school programs are important because they use specially created maps. These maps sought to instill in children the concept of being an Ottoman state-citizen, and they are united inside the confines of the Ottoman country. The use of colors on the map and the emphasis on borders were the moments at which the Ottoman worldview attempted to be implanted in people’s minds.

According to Lewis, advancement in education was the driving force behind all of the improvementsof the time. The increasing number of schools in the country was the hallmark of the Hamidian era’s success. The school enrollment rate increased by 7% throughout this time period. When Abdulhamid II succeeded to the throne in 1876, there were four schools for teacher education in addition to 18,490 elementary schools, 253 secondary schools, and four universities. However, towards the end of Abdulhamid’s reign, the country had 32 teacher training institutions, 5,000 primary schools, 619 secondary schools, and 109 high schools.Zurcher, on the other hand, claims that the rationale for opening a huge number of schools is the necessity to educate and provide bureaucrats for a state that lacked them. In the realm of Istanbul, 18 new girls’ schools had opened, demonstrating Abdulhamid’s concern for women’s education. Darulmuallimat graduates were compulsorily appointed to newly opened schools, which eventually gave rise to the brilliant women thinkers of the second constitution and Republican eras.

Some argue that the overall goal of Abdulhamid’s education strategy was to create an educated middle class that was at peace with the dictatorship and the Sultan’s official philosophy. People would become obedient, loyal to the palace, and sophisticated as a result of their education and political indoctrination in the schools. The spread of modern education facilities in the rural areas led to the emergence of a new educated class that brought an alternative way of thinking when it compared to the aydins of Istanbul. The ideological conflict between the center and rural could be seen obviously with the results of new schools.

Conclusions:

The Ottoman state’s public education system has been modernized for nearly a century, with various attempts to observe parapraxis. Cevdet Pasha, a well-known writer and educator of the modern era, attributes the failure of these projects to two main factors: attempting to implement the new system without first establishing the infrastructure and assigning ignorant and inept personnel to crucial positions in these ventures. Without witnessing the consequences (as graduates’ work and raised generations) and larger implications of education in historical continuity, we cannot answer the question of darulmuallimin, whether it was a successful trial or not in terms of updating the educational system. Darulmuallimin, on the other hand, marked the beginning of a vast social transformation that would reveal its strength in the fundamental foundations of Turkey’s nation state and others in the Balkans and the Middle East. Education is a long, and laborious process that has affected societies in ways that are difficult to assess. Still, Darulmuallimin was one of the most effective trials of Ottoman strategists, whether they were sultans or bureaucrats.Darulmuallimin, its lecturers, and pupils presented a new perspective that could help Ottoman civilization adjust to the contemporary world. As a result, the experiment of educational modernization and Darulmuallimin was one of the effective outcomes of elevating the aydıns and leaders of primarily Turkey’s but also the foundation of ex-Ottoman nation states’. Darulmuallimin therefore became a very typically symbol of today’s modern education’s revolutionary path in the Middle East, Anatolia, and the Balkans.

Abdullah SAK

Bibliography

-1316 Salname-i Maarif-i Umumiye

-1317 Salname-i Maarif-i Umumiye

Abdülhamid, II. (Ali Vehbi Bey). 1999. Siyasi Hatıratım. İstanbul: Dergah Yayınları.

Akyüz, Yahya. 2008. Türk Eğitim Tarihi, M.Ö. 1000 – M.S. 2008. Ankara: Pegem Academy Press.

Alkan, Mehmet Ö. 2004. “İmparatorluk’tan Cumhuriyet’e Modernleşme ve Ulusçuluk Sürecinde Eğitim” Osmanlı Geçmişi ve Bugünün Türkiye’si. Edited by Kemal H. Karpat. İstanbul: Bilgi University Press.

Bilim, Cahit Yalçın. 1984. Tanzimat Devrinde Türk Eğitiminde Çağdaşlaşma(1839-1876). Eskişehir: Anadolu University Press.

Cevat, Mahmut. n.d. Maarif Nezareti Tarhiçe-i Teşkilât ve İcraatı.

Deringil, Selim. 2002. İktidarın Sembolleri ve İdeoloji, II. Abdülhamid Dönemi (1876-1908). İstanbul: YKY Press.

Er, Hamit. 2001. Osmanlı Devleti’nde Çağdaşlaşma ve Eğitim. İstanbul: Rağbet Press.

Ergin, Osman Nuri. 1977. Türk Maarif Tarihi C. I-II-III. İstanbul: Eser Press.

—. 1977. Türk Maarif Tarihi Cilt 1-2. İstanbul: Eser Press.

—. 1977. Türk Maarif Tarihi Cilt 3-4. İstanbul: Eser Press.

Fortna, Benjamin C. 2005. Mekteb-i Hümayun: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nun Son Döneminde İslam, Devlet ve Eğitim. Translated by Pelin Siral. İstanbul: İletişim Press.

Gencer, Bedri. 2008 . İslam’da Modernleşme (1839-1939). Ankara : Lotus Press.

Haldun, İbn-i. n.d. Mukaddime. Edited by Pîrîzâde Mehmed Sâhib – Ahmed Cevdet Paşa.

İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin. 1992. Osmanlı Bilim ve Eğitim Anlayışı, 150. Yılında Tanzimat. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Press.

—. 1992. Tanzimat Döneminde İstanbul’da Darülfünun Kurma Teşebbüsleri. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları.

İlikli, Yeliz. 2010. Darülmuallimin – Darülmuallimat. Ankara: Gazi University.

Kafadar, Özkan. 1997. Türk Eğitim Düşüncesinde Batılılaşma. Ankara: Vadi Press.

Karpat, Kemal. 2009. Turkish Education History. İstanbul: Timaş Press.

Kayaoğlu, Tacettin. 2001. Mahmut Cevat İbnü’ -Şeyh Nafi: Maârif-i Umûmiye Nezâreti Târihçe-i Teşkilât ve İcrââtı -XIX. Asır Osmanlı Maârif Tarihi. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye Press.

Koçer, Hasan Ali. 1991. Türkiye’de Modern Eğitimin Doğuşu ve Gelişimi. İstanbul: MEB press.

Kodaman, Bayram. 1988. Abdülhamid Devri Eğitim Sistemi. Ankara: 1988.

Lewis, Bernard. 2000. Modern Türkiye’nin Doğuşu. Translated by Metin Kıratlı. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Press.

Nurdoğan, Arzu Meryem. 2005. Osmanlı Modernleşme Sürecinde İlköğretim (1869-1922). İstanbul: Unpublished Doctorate Thesis – Marmara University Social Sciences Institute.

Ortaylı, İlber. 2003. İmparatorluğun En Uzun Yüzyılı. İstanbul: İletişim Press.

Özcan, Abdülkadir. 1992. Öğretmen Yetiştirme Meselesi, 150. Yılında Tanzimat. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Press.

Öztürk, Cemil. 2014. Darülmuallimin. Ankara: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslam Ansiklopedisi.

—. n.d. İslam Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 8. Ankara: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı Press.

Paşa, Ahmet Cevdet. 1976. Tarih-i Cevdet. Edited by Mümin Çevik Dündar Günday. İstanbul: Üçdal Press.

Sakaoğlu, Necdet. 2003. Osmanlı’dan Günümüze Eğitim Tarihi. İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi University Press.

Sarıkaya, Yaşar. 1997. Medreseler ve Modernleşme. İstanbul: İz Press.

Sırma, İhsan Süreyya. 2000. Belgelerle II. Abdülhamid Dönemi. İstanbul: Beyan Press.

Somel, Selçuk Akşin. 2001. Modernization of Public Education in Ottoman Empire 1839-1908, İslâmization, Autocracy and Discipline. Brielle: Brielle Academic Publications.

Şentürk, Recep. 2008. Türk Düşüncesinin Sosyolojisi, Fıkıhtan Sosyal Bilimlere. İstanbul: Etkileşim Press.

Ülken, Hilmi Ziya. 2001. Türkiye’de Çağdaş Düşünce Tarihi. İstanbul: Ülken Press.

Zurcher, Eric Jan. 1993. Turkey: A Modern History. London: I.B. Tauris Press.